Silicon Valley provocateur John C. Dvorak in his Woefull Tale of the $100 laptop on Market Watch is calling One Laptop Per Child "a massive exercise in futility"..

He first questions the need for computing in the developing world:

To summarize, there are only so many hours in the day, and we should not be wasting them on this kind of naïve feel-good showboating. Let's face it: These high-tech gems are a laughable addition to a mud hut. […]To the surprise of some, this is where I disagree with Dvorak and actually completely agree with OLPC. The developing world needs access to information, what cell phones and radios deliver in limited quantities and the Internet can deliver in a massive, almost overwhelming self-directed flow. Access to information is the key to creating stable, robust, and wealthy communities.Perhaps the organization should be thinking of the hand-cranked generator as serving [to power lights] alone and not computing. Lights, along with cellular phones and radios, seem more important than laptops.

In that need, Nicholas Negroponte's ego-driven hype has served an effective purpose. His often grandiose dreams have invigorated the development conversation with a dose of much-needed technology talk.

Talk that has captured mind share. Unfortunately, maybe too much mind share. Mind share that Market Watch article contributor and Stanford journalism lecturer G. Pascal Zachary feels is wasted:

"The real problem is lost mind share. The people are harmed because these sorts of schemes are sopping up mind-share time of the people who might be doing something actually useful."So what does John C. Dvorak think is a better use of people's time, what the One Laptop Per Child contributors should be doing?

American e-waste

We should be spending our energy trying to figure out what to do with the hundreds of millions of computers that are junked rather than making more junk.Actually, Mr. Dvorak, only someone who only looks out from a five-star hotel window would think that junked high-end computers, like those tossed out by Americans every day, would be suitable for the developing world.

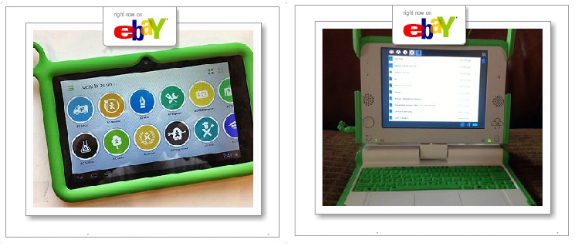

Standard office computers would be junk themselves in the harsher, more demanding developing world environment. In that environment, OLPC's technology is not only more suitable, it's a revolutionary leap that will transform computing in extreme environments. And a very worthy use of everyone's mind share.

The main mind-share shame is that not enough of it is focused on building realistic and affordable Children's Machine XO pilot implementation plans, instead of proposing budget-busting implementation miracles.

Mr Dvorak seems to be reasoning that since poorer countries cannot possibly make use of technology then we shouldn't be using our 'mind share' to provide educational tools to children.

He quotes G. Pascal Zachary on how important networking is to computing. Obviously Mr Zachary didnt know the laptops have wireless networking built in. In a class situation where all students are in the same room and the teacher has the study curriculum on their computer (this could even be in the form of a USB flash drive) you pretty much have 'School-In-A-Box'.

I cant help thinking that Dvorak has put very little thought into his article since he seems to quote Zachary in a large part of it. The idea of 'Mind Share' would suggest that not only 'Should we do this?' but instead demands that 'We must do this!'.

The questions we need to focus on are:

Do computers help in education?

Will poorer countries benefit from computer education?

Can the education infrastructure be implemented?

Is the $100 laptop cheap enough?

I feel that deployment of computers in schools is much like the advent of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1440. We will not only see literate adults in Third World countries in years to come but they will have access to information about the wonderful World we live in.

The concept of "access to information" has always struck me as too static - as if the information were kept hidden somewhere and only a few people who could get at it could become wealthy, etc.

My involvement with the Community Memory Project starting in 1972 showed me that people create as well as use the information that is most important to making a community function. "Access to information" in this context really means "access to each others' information" - something more akin to the operation of the telephone than the library.

This is why I counterpose "one laptop per child" with "one telecentre per village" (the British spelling is intentional - see my blog). Bring in the phone (with computer attached) and farmers and small producers can actually participate in the marketplace - incomes have been shown to rise as a consequence. Then there'll be support for laptops, both infrastructural (the Internet will have come to town with an economic model that works) and as mindshare.

I've known John Dvorak for many years and am not surprised to see him pop off like this. Zachary, however, does articulate my fear that OLPC will grab mindshare in a negative way and screw up others' chances to implement computer-based systems and tools in the developing world.

Please, let's try to draw distinctions as this drama moves forward and not accept simplistic analyses put out by Dvorak's ilk.

You have fallen into Dvorak's trap. He doesn't write about what he believes, he writes about what will rile up his readers and generate lots of controversy and hits on his articles. This blog post was just what he wanted.

They thought the laptop per seventh grader worked in Maine when they tried it in 2000. At first the teachers were 80 percent opposed. After two years, the teachers were 100 percent in favor. And the truancy rate had dropped to near zero.

It can work. Not guaranteed but possible.

If orders for five or ten million are prepaid, a billion dollars or more, then we will be on our wqay to the biggest education experiment in history. And a major turning point in the third world.

Lee's Community Memory project was a shining light, but by comparison, this is another sun in the making.