MasterCard has an advertising campaign that the ICT4D Jester finds ingenious. They all go something like this: "Water glass: $5″ (shot of cute kid turning off water while dad brushes teeth at sink); "energy saving bulb: $4″ (cute kid recommends power-saving bulb at store); "reusable bag: $2″ (cute kid returns plastic bag at cash register); "helping dad become a better man: priceless" (mom looks on approvingly as dad appears to sigh reluctantly). The tagline is... "There are some things money can't buy. For everything else there's MasterCard."

This is sheer brilliance. Here's a product -- the credit card -- that is all about debt, rampant consumerism, and extraction of interest payments, and the ad turns it completely around. Though the script says, "there are some things that money can't buy," the message they're sending is "actually, you can buy them with MasterCard." The sequence leading up to the priceless things -- usually a precious emotional moment with a loved one -- is usually stuff that you can buy, and in the ads, they're carefully sequenced to set the stage for the emotional moment.

The tagline is also a deft feat of doublespeak. An association is made that links the things money can't buy with MasterCard. They say nothing logically incorrect. Yet, the implications are deceptive. If you watch these ads without the logical filters of your frontal cortex, you walk away with a warm, fuzzy feeling and an urgent desire to fill out a credit-card application form.

The Jester has a conspiracy theory that Nicholas Negroponte wrote these ads for MasterCard. His fingerprints are all over these ads! Feel-good imagery, platitudes you can't disagree with, and juxtaposed associations that give the illusion of a tightly constructed logic despite the absence of one.

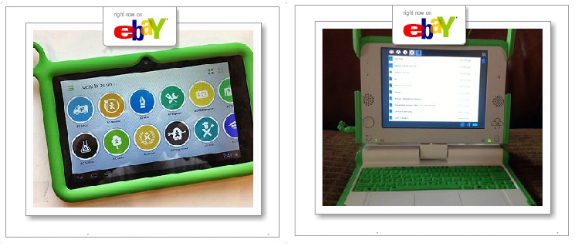

In this post, the Jester deconstructs Negroponte's seductive rhetoric. Many others have critiqued the OLPC project (for example, http://www.olpcnews.com/ and http://edutechdebate.org/), but this post specifically deconstructs the rhetoric itself. The Jester feels no compunction using Negroponte as an example and a target, since he is the most visible of PC pushers, the least open to criticism (and therefore, beyond change through constructive engagement), and extreme in his stance.

The Jester also recognizes the futility of trying to persuade technology-for-education champions who do what they do because of deep-seated pathologies beliefs that are unlikely to change with any amount of rational discussion. This post is instead dedicated to (1) educational decision-makers who are considering OLPC (or computers for schools) and (2) people working for non-technological basics in schools, and who need ammunition to fight the seductive rhetoric of technology pushers. The points are made primarily for primary and secondary education in international development, though the arguments often apply beyond. So, without further ado...

- Negroponte Point 1: Children are innate learners.

- Jester Counterpoint: Even innate learners need good adult guidance.

Discussion: Hear the MasterCard music in the background? Of course, children are innate learners! Who will disagree? But, being an innate learner is one thing, bootstrapping any significant part of primary and secondary education without good adult guidance is another thing entirely.

The rhetorical trap here is to go from "innate learners" to self-contained learners who only need the right materials to learn. No sane parent would send a kid to a school where the pedagogy is to leave children in a room unsupervised with laptops all day and nothing else. Yet, plenty of good parents will send a kid to a school with top-notch teachers and no computers. Competent adult supervision - i.e., teachers - is a critical component, and cannot be replaced by technology. If that is missing, providing it is the first order of business, contra Negroponte.

Some people can't shake the belief that children just need to be left alone with the right educational aids to learn everything they need. But, if everyone were such self-sufficient educational bootstrappers, why not simply hand out Erector Sets? (What is "programming," after all, but virtual engineering?) And, if you take that argument further, children shouldn't need anything beyond mud, sticks, and stones to learn. Those materials are enough for serious creative design, peer learning, and complex engineering.

- Negroponte Point 2: A laptop is the perfect complement for an innate learner.

- Jester Counterpoint: A laptop is a very versatile educational toy. Like any toy, children can learn from it or not. For the long haul, what matters is, again, good adult guidance.

Discussion: Believers of computers for education believe in its capacity as a universal machine. There is no better technology for storing, processing, displaying, and allowing interaction with information. So far, so good. Negroponte adds a further point that programming a computer is like teaching (it). (The Jester disagrees, but let's suppose this is also true for the sake of argument.) Combined with the cliche about teaching being the best way to learn something, all this suggests that computers are the best tool for learning. This is yet another sleight of hand, with MasterCard elegance.

The underlying issue is that education requires prolonged motivation, either internally generated or externally inspired. Children have a lot of internal curiosity, true, but that requires good adult guidance to keep alive for the long haul required for a good education. Today's technology cannot provide that motivation. On the other hand, there is plenty of evidence that learning is a social process that thrives due to human encouragement, approval, guidance, direction, etc., and all preferably from adults who are caring, educated, and attentive.

As for "teaching" laptops through programming, programming does require deep understanding, but how does a child acquire that deep understanding in the first place? The Jester would venture that in the history of computers in education, no child left alone with a computer has ever gone from being able to count to doing polynomial algebra. It's not that software couldn't be written to guide a student through this process. It's that adult guidance, approval, and support is still necessary. (If any software comes close to doing this, it's probably software developed by Carnegie Learning. But, they are so conscious of the need for good adult supervision, that they won't sell software without the right pedagogical framework in place.)

To suggest that a laptop is enough for a child to learn the substantial content of formal education is basically to say that every child has within themselves the capacity to rediscover the significant portions of math, literature, history, science, etc., that took centuries, if not millennia of the world's greatest thinkers to discover. With or without a laptop and the Internet, this is a great stretch of imagination.

- Negroponte Point 3: Education isn't about drilling and rote learning. It's about creativity and social interaction with peers. Laptops transform rank-and-file classrooms into creative learning environments.

- Jester Counterpoint: Educational quality ranges from (1) very bad, to (2) decent education possibly by rote, to (3) superior education that raises brilliant, creative, self-motivated lifelong learners. Each of these steps requires an upgrading to a stronger school system, with better teachers and better administrators. Superficial appearances of jumping from (1) to (3) with technology are illusory.

Discussion: More MasterCard fluff. If there's a kernel of truth here, it's that if you do introduce a bunch of laptops into a classroom, you'll immediately get a lot of laughing children and what appears to be constructive chaos. That's beautiful to see when you do short-term drop-in visits to classrooms, but in the long run, someone has to settle the class down and teach long division. Real education requires ongoing discipline, and by that the Jester doesn't mean knuckle-raps-with-a-ruler discipline, but the kind where students are consistently encouraged and cajoled to learn even the subjects they aren't naturally drawn to and in the process learn self-control and perseverance. Again, for most children, this requires good adult supervision.

Among liberal elites, there's often a great emphasis on creativity and "critical thinking". But, these folks are arguing about getting from (2) to (3). Even that leap requires better adult supervision, not more technology, but in the rush to get to (3), it's pointless to go for what looks superficially to be (3) when the reality is often stuck in (1).

A related point is that (2) can get you quite far. This point gets deep into pedagogy, and education research hasn't yet figured it all out, so the Jester will rely on examples. Japan has an educational system that is based on rote learning, which the Jester has personal experience with. Even advanced mathematics is learned by rote, where students do a lot of memorization and learn how to solve problems by learning algorithms for specific patterns of problems.

Now, you could criticize the system and say that it suppresses creativity and autonomy, and those critiques would be partially valid. But, you simply could not say that the Japanese educational system is a failure on the whole. Japan's literacy rate is among the highest in the world (higher, certainly than the United States); it's the third largest economy in the world even after a prolonged recession (and #1 and #2 have much larger populations); and life expectancy there is generally in the top two (competing with Iceland). If that kind of education could be delivered worldwide, we'd wipe out illiteracy in a generation.

The Chinese and Indian educational systems are also based on rote learning. Of course, not everyone is getting a quality rote education, but those who do often end up in U.S. universities, and many casually outdo their American peers.

The Jester's own hypothesis is that the most critical aspects of education aren't the knowledge gained. They're actually the meta-lessons children learn when they're put in an environment in which they have daily opportunities to learn that effort leads to reward. 12 years of individual experience with a system that rewards you when you inject effort can lead to a firm belief in effort when you grow up. The alternative is to grow up believing that luck is the critical element to success, as children of poorer families apparently did in the 1960's Coleman Report. The right meta-lesson can be learned even in a rote learning environment, as long as, again, it has good adult supervision.

In short, a good rote education is far, far better than no education or a bad education, and it cannot be replaced with a non-human pedagogical alternative. To believe that a quality education can be replaced by a laptop is to believe that the hours we spent on our own education away from PCs wasunimportant. Very unlikely.

- Negroponte Point 4: OLPC only costs a dollar a week per child.

- Jester Counterpoint: A dollar a week is already expensive for most developing countries. And, in any case, the total cost of technology is multiples of the cost of hardware. A good rule of thumb is that total cost is 10 times the cost over the lifetime of the hardware.

Discussion: MasterCard, MasterCard, MasterCard. First, if a dollar a week sounds cheap to you, you haven't spent enough time in the developing world. The Indian government spends no more than $200 per child per year on education, and most of it goes to teachers' salaries. Government schools often lack toilets, walls, and even buildings. And, this is all in a country where tax revenue is doing quite well, relatively speaking. Plenty of less developed countries spend less than the dollar a week per child on education, so OLPC is effectively saying, "get rid of your schools, just distribute laptops."

Second, a dollar a week for a laptop is likely an underestimate for the total cost of ownership. This suggests that a $188 laptop would last four years, and require no other expense. Who is paying for electricity and connectivity? Curriculum integration and teaching training? And, what about maintenance? In Uruguay, where OLPCs have been distributed to all of the countries children, they find that as much as 30% of the laptops are out of commission at any given time and waiting to be repaired or replaced, and this in the first year of the program. Unless they're replaced (which incurs a cost), 30% a year means that in four years, only 20-25% of the laptops will remain. There's some funny math here. (For more, see http://www.olpcnews.com/sales_talk/price/. The Jester thanks Wayan Vota for the pointer.)

- Negroponte Point 5: Rich kids have laptops, why should poor kids be denied?

- Jester Counterpoint: Rich kids are driven to school in Mercedes Benzes, why should poor kids be denied?

Discussion: By now, you should be able to see the MasterCard doublespeak. This again sounds great out of context, but in a context where the poor kids are also missing nutrition, vaccines, clean water, etc., this rhetoric makes no sense. Rich kids have a lot of things that poor kids don't. Among those things, which should be prioritized?

Definitely not laptops.

- Negroponte Point 6: 2 million OLPC laptops have been sold.

- Jester Counterpoint: Billions of cigarettes have been sold.

Discussion: Economists call this the "market test" fallacy. Just because a lot of suckers have bought a product doesn't mean it's good for development. Cigarettes and alcohol are best sellers, but it's not clear that the developing world should buy more of them.

The subtler point is that educators often rush to buy technology, because it seems everyone else is doing it, too. Gosh, educators should be the first to recognize and deflect bad peer pressure when they see it.

- Negroponte Point 7: It's not worth doing, if the impact has to be measured.

- Groucho Marx Counterpoint: "I don't care to belong to any club that will have me as a member."

Discussion: Negroponte said this in a panel, in response to an audience challenge to have J-PAL do a randomized controlled trial of OLPC. The Jester believes Negroponte meant that unless something has a huge uncontested benefit, there's no point in doing it. But, this is MasterCard hogwash of the highest order. The benefit of laptops in schools and at home is actively debated. Research results are consistently mixed and often negative. This puts it in a category where evaluation becomes necessary. No chance of Negroponte dropping OLPC because of that, though.

- Negroponte Point 8: Laptops are like vaccines, vaccinating children against ignorance.

- Jester Counterpoint: Global telecommunication is like a vaccine, vaccinating the world against hatred and war. (Not quite, right?)

Discussion: Sounds great, but laptops are not vaccines against ignorance. Just because someone famous says it doesn't make it true. It would be nice if we could inoculate children against ignorance, but that's a shortcut we will probably never find.

Vaccines are an amazing technology, and laptops are simply not their equal for the purpose of education. It takes a vaccine from days to months to work, and it requires no effort on the part of the child. A good education requires one to two decades, and there is simply no evidence that a child alone with a laptop, even with other laptop-encumbered peers, will learn what we expect of a well-educated adult.

- Negroponte Point 9: Kids teach their parents to read with the laptops. The laptops change classroom dynamics so that teachers are learning from the kids.

- Jester Counterpoint: Hitler was an effective leader. Hitler loved his dog.

Response: A few heart-warming anecdotes aren't enough to demonstrate net total value. In fact, for every positive anecdote about OLPC, there are plenty of negative ones. There are stories of piles of OLPC laptops gathering dust, or being stolen, or breaking and remaining unrepaired, or threatening teachers who then confiscate the laptops, etc. Computers overall are known to be distracting in the classroom, unless they are carefully integrated into curriculum. Given that there is a cost to laptops, the laptops have to show significant positive benefit to make sense. The evidence that exists is consistently neutral or mixed.

One response to this is that anecdotes can be verified or countered with an experimental trial. Why not measure the effect laptops have on parental literacy? Why not see what students learn more or less of after a year with the laptops? If children in Afghanistan learned more with a laptop than with an equivalent cost used to run a school, that would instantly silence critics, the Jester included.

Unfortunately, the real issue isn't evidence. It's the human propensity to emphasize isolated stories over dry statistics. As P.T. Barnum said, you can fool some of the people all of the time. The capacity for reasoning is a flimsy structure compared the human affinity for narrative.

The solution for *that*, of course, is a good education. Unfortunately, it's not enough for education ministers to have their own laptops, to give themselves the education required to think critically about laptops.

In a future post... The four things that computers are good for in education, and why none of them should be a first priority for poorly run schools and schools with limited budgets.

Did the Jester leave out any other points to counter?

This post was previously published as How OLPC is like MasterCard by the ICT4D Jester

A study by Nobel Laureate Carl Wieman shows that method is more important than teacher. http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20110512/ap_on_sc/us_sci_teacher_or_tools

A noteworthy vote for what OLPC is trying to explain by a renown teacher and scientist.

We are learning in Cambodia how both rote and creative hands on learning combined is getting the job done! Sometimes working with the cultural system is better than fighting it.

"They're actually the meta-lessons children learn when they're put in an environment in which they have daily opportunities to learn that effort leads to reward. 12 years of individual experience with a system that rewards you when you inject effort can lead to a firm belief in effort when you grow up."

Now this quote is saying that education is a fraud: Children must make tremendous sacrifices to learn irrelevant things bacause that sacrifice is the goal of the excercise.

If this means you think education should be based on lying to children about the relevance of what they do, I have my reservations.