[sigh] There's nothing like bureaucratic bafflegab. Fortunately. Does this mean anything to you?

Some research indicates that countries are pursuing a wide range of strategies and goals to encourage the use of computers and information technology for instruction, suggesting that there might be much to learn in this area from international benchmarking.

Wagemaker, H. Highlights of Findings from Major International Study on Pedagogy and ICT Use in Schools. 2006.

The purpose of bafflegab is well-known: to cover up the fact that you have nothing to say, and don't know what you are talking about. Well, I don't speak this language all that well, mostly because I do have something to say, and I do have some idea of what it's about. But I can read it well enough, and tell you what it means in plain English.

My translation, mostly to words of one syllable, makes it clear that the essence of this statement is ignorance. "We hear that there is a lot of it going on (computers in schools around the world), and perhaps we should find out more about it." But in fact, they have done pitifully little, and most of them don't know what the questions are. Worse yet, after raising the issue, this report goes on to say precisely nothing about it. (It is worth noting that a large fraction of all government communication comes down to the same single sentence, with only the topic changed. From this sentence alone, it is impossible to tell whether the purpose is actually to find out something and to act on it, or to put off or prevent action.)

So here I am to tell you something about it. The information is there, if anybody really wanted to look for it.

The passage above is quoted in a report from The Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO), "a nonpartisan, nationwide, nonprofit organization of public officials who head departments of elementary and secondary education in the states, the District of Columbia, the Department of Defense Education Activity, and five U.S. extra-state jurisdictions."

The report is Benchmarking for Success: Ensuring U.S. Students Receive a World-Class Education. It's almost complete rubbish. Warmed-over platitudes, with no substance.

I say almost, because it gives lip service to two important ideas. First,

At the same time, the U.S. ranked high in inequity, with the third largest gap in science scores between students from different socioeconomic groups.

The essence of our current problem. But it comes up against another problem: we are not ready to discuss it seriously. The remedy is obvious: put more resources into education for the poor and otherwise disadvantaged. That idea is barely on the table in our current political climate--maybe for next year. And that's a major improvement compared with the previous climate. The report itself makes no recommendations.

Second,

Benchmarking is the practice of being humble enough to admit that someone else has a better process

So far, so good.

and wise enough to learn how to match or even surpass them.

Lost it there. What good is pretending to be humble starting out if you show you don't mean it one second later? No, if you are actually humble and wise, you start a long way back, where you actually are, not with matching or surpassing. You can't assume that you will outdo everyone else, because generally you can't. Nobody can. Oh, sure, you might be able to be the best at something. Whatever you look at, somebody is best at it. But you can't get there just because you decide to. There are little matters of political will, talent, resources, support from others, long and hard work, and a bit of this, that, and the other besides.

Most of all there is the competition. All of those other countries are busy catching up with the US in other areas. The US isn't behind only in education. And even where the US has had a lead, that lead may be shrinking, and it may be shrinking specifically because of one or another of our strengths, as happened in the automobile industry. Try this:

If a machine can score computer-based writing assessments effectively, should we care how the machine does it? - Educational Testing Service

ETS is of course in the business of selling standardized testing services and materials. The US has long been a leader in standardized testing. But that means that we test only what we know how to standardize. What about everything else? What we know how to standardize in education is limited to what we thought we were teaching, and is a crude measure of how much of it the student has learned. What about the ability to learn something new, without being taught? This is the most valuable skill a student can have, but we neither teach it nor test it. We don't actually know what it is.

This sentence from ETS is in a much more sophisticated version of bafflegab. Instead of verbal obfuscation, it relies on misdirection of ideas, in particular on asking the wrong question and making it seem reasonable.

My answer to the ETS question is, first, that the assumption in the question is invalid, and necessarily invalid, and that the rest of the question is therefore irrelevant. (Short of Strong AI, that is, at which point we have other problems to deal with, because we may have just made ourselves irrelevant.) However, the answer to the second part is still a resounding, Yes, we should care.

This isn't the first time this error has appeared in the world. The Ming Dynasty Chinese government standardized the literary exams for its civil service in the form of the "Eight-Legged Essay", resulting in the most soul-crushing education system in the world for more than 500 years. These essays were required to have a tightly specified form in eight sections, for ease of grading. The structure of individual sentences was prescribed, and the number of sentences in each section.

Almost all of the rest of the world followed the later example of Prussia, which reorganized its public education system on factory automation lines in the 18th century. A large part of the project consisted of dumbing down each subject and limiting its scope as much as possible, and concentrating the minds of teachers and students on only what was in the textbooks, and only the pre-approved right answers to questions in any subject. To be sure, the Universities encouraged research among graduate students and faculty, but only after making sure that nobody would attempt to do research outside of his assigned subject area. (Women didn't enter the question at the time.)

There is no question in both cases that the resultant dumbing-down of education was intentional. Neither China nor Prussia wanted creativity or outstanding competence in their civil services. They wanted intelligence, but only highly domesticated intelligence that would follow orders without question, and a level of competence sufficient for doing what was expected, but no more. Creatives were shunted into the arts, or into specialties where they would not interfere with the running of government.

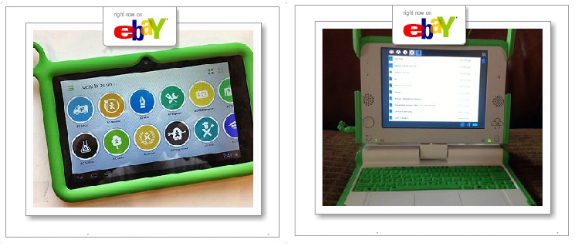

We have begun to understand, here and there in the world, how to help children learn how to learn, and some of us have begun to want to do it, and to think about how to break out of these government-imposed straitjackets. Seymour Papert raised this question more than 40 years ago, in his book Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas. He wasn't the only one, of course, and he wasn't even the first, but I single him out because much of the Sugar software for the OLPC XO and other computers is built on his work, and on 40 years of Alan Kay's Smalltalk, as well. But we clearly don't all have this idea, and it is equally clear that most people involved in education have not gotten out of the old models.

The truly astonishing thing about using XOs and Sugar is not the results on standardized tests (which are excellent in some cases that have been measured) but their transformative effects on society and on the very idea of education, particularly their ability to lead teachers to new models of education.

The change in Ethiopian trials from pure rote learning to discovery, and from treating questions as insults to deciding to put question time into lesson plans is the best documented. We have seen particularly good results for disabled students in the US. Bryan Berry has described a simple counting program that brought Nepalese children up several grade levels in arithmetic.

I raise these issues because I do want to teach children more than we have in the past, and allow them to learn as much as they want. To that end, I have been talking with politicians and educators about getting together on one-to-one computing research, development, and deployments. I'm getting a good response in places that I know are ahead of the curve, but I know that we will run into all the obstacles to education reform that have ever been, because they still exist in much the same forms, for precisely the same reasons. Large segments of the population are afraid of children learning how the world really works, and getting together to do something about it.

It might be different this time, because One Laptop Per Child with Free Software means that all of the children can have the same tools, and that we can integrate those tools into the curriculum for the first time, at less cost than printing and distributing paper textbooks. The fact that the information and tools are Free means that bureaucratic committees and regulations cannot block them out from the classrooms.

It will only be different in the way we hope if we make it so. So who would like to go talk with local politicians, school boards, PTAs, and the rest of the stakeholders? We can work out appropriate pitches for different audiences together, and we can create a national and global framework to make it happen.

Now, I know that the usual naysayers are out there. For them I have the same question as always. Would you rather curse the darkness, or teach children to make candles?

cherlin writes

"The truly astonishing thing about using XOs and Sugar is not the results on standardized tests (which are excellent in some cases that have been measured) but their transformative effects on society and on the very idea of education, particularly their ability to lead teachers to new models of education."

Pure lies along with the dishonest "bafflegab" he is so quickly criticizes in others.

There are no DOCUMENTED cases of "excellent results on stadardized tests", just like there NO EVIDENCE of the XO having any sort of "transformative effects on society".

C'mon, show some intellectual honesty. Speak the truth. The case for the XO providing benefits for education can be made without these blatant lies.

Thanks, Irv. As always, coming from you this is high praise.

Indeed, Edward. A good article deserving of praise.

"Would you rather curse the darkness, or teach children to make candles?"

Your examples from China and Prussia can be extended by many other countries, as you write. So I am afraid the answer will be much too often the Former.

Except that cursing will not be allowed.

Many adults do not accept reality themselves, so how could they tolerate their children to face reality square on?

Still, we will have to accept that the parents have the ultimate say in how children are to be raised. Trying to impose ones view of the world onto other peoples children is a recipe for disaster. Quite literally.

Winter

Ed, I know you are the exception. However, "They wanted intelligence, but only highly domesticated intelligence that would follow orders without question, and a level of competence sufficient for doing what was expected, but no more" describes perfectly the managers of many so-called constructi*** initiatives, precisely seen because "the information and tools are Free" does not happen, using your terminology, sunk in their "bureaucratic bafflegab".

Why do you think it is so? why is it that it seems to be so hard to get information from OLPC, while they are decidedly and publicly desirous to call themselves THE inheritors to Papert et al.? Ceibal? Other OLPC-connected initiatives? The other guys you point at offer information, maybe not the kind you like, but it is out there.

M & E (monitoring and evaluation) is important because it is not about the tongue of angels, but about facts that we need to be able to share, that decisions get made, policies implemented, and kids get a chance to use these tools. It is also that way that best practices get discovered and refined, hopefully with less nonsense than what you share about Prussia and China, because you also know that random speculation and trial will not get us there. Even convicted evolutionists believe that even if they are right it takes a biiiiig loooooot of time for randomness to get somewhere useful, the meanwhile being mostly a story of failed mutations.

Now, this is not a criticism of you, Ed. AFAIK you always have been most open to share information and even ownership of initiatives, but it is a criticism of those who think the XO / Sugar / OLPC is right just because they improper syllogisms, and have not much evidence to prove their point. And as you point out, the Ethiopia report is good as reports go, but it strongly proves that the current modus operandi of OLPC and friends is deeply flawed, much work is still needed, and so much more. Interestingly, by now it is also quite dated, with little that is any better yet.