As with any volunteer-based concept worth its salt, it would appear we are not quite in agreement here as to how one laptop per child initiatives should be implemented. Discussing what hardware platform and what operating system we should use sometimes pales in comparison with debates on the inherent ideology of education that should be pursued.

The very fact that I, personally, assume that our effort should necessarily be a volunteer, grassroots, community-based movement has very strong opposition from those who are running projects from a top-down, central-government perspective.

goals, anybody?

We generally agree on some concepts about "what is good": education is good. ICTs are good. High ratio of computers is good, thus one-to-one. These notions tend to cascade: one laptop per child is a good way to do ICTs for education.

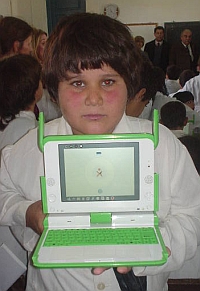

Some of us see as great that the XO hardware is resilient, needs low power, and thus maybe is or at least was the best platform for ICT4E.

Where we collectively hit the fan with out conversation tends to be on how and what we want to achieve. Is it to empower the teachers to do better what they are doing? Is exploring the internet a better way to learn, instead? Should we bow to the ignorance of high level officials who might approve out project if we offer them portholes? Should we take uncompromising stands? What is "good education"?

a few facts

As anybody else, I like to think that my opinions are based on facts, on reality. Hey, by the way, this is Yama Ploskonka writing. Also by the way, this is an opinion piece, though I hope that a bit more conciliatory than some of my pronunciamientos have been. So, back to the facts, or at least those I have on hand right now forming my current opinions.

Let's assume we agree that education is good, and also that within everything that goes under the name of education, some is better than other. Now, this is not an idle exercise in meta-ethics. Figuring out what is "best" in education tends to have huge outcomes at the national level and personally, as anyone who has suffered their way through some competitive examination knows.

While socio economic background is the best indicator for college and university performance, most of us have had to take the SAT, GREP, or the South African "Matric" (with poignant documentary), or some national alternative (Google search).

Let's Imagine for one moment that reality is different. That we are in some alternate dimension where initiative is valued, creativity prized, and bullying of geeks is no more. Where entry to the University does not rely in mastery of certain "facts" or ways to say them, but on Something Miraculous, that comes about from independent exploration of the internet and creativity, basically what is proposed by OLPC, by Ceibal, and other such initiatives that follow the dictates or share the ideology of OLPC. One problem: it is not this reality.

reality

Reality is that pretty much everyone who actually decides who is allowed access to high-influence, high-performance, and high-paid careers wants scholastic achievements and respect of precedence as hallmarks on a piece of heavy paper that has the graduate's name on it in fancy lettering. I am not debating whether the ivory towers are wrong, self-centered, blind to progress... Maybe they are. But that is a moot point, since universities make the rules.

Yes, maybe our OLPC graduate has a career as an industrialist, merchant or artist, but unless he also knows his "facts" and has proved it after 12 years or so of classes, he will be barred from becoming a doctor, engineer, lawyer or any kind of scientist or "professional".

are we getting there?

So far Sugar and OLPC-based initiatives are not focused toward kids getting better scores for the SAT, Matric, CET, XAT, or any other national variant. Yes, certainly, it is bad to educate to the test, isn't it? Except when you are the kid that has to pass the test.

I do not believe that those who go for "la tête bien faite" (well rounded education vs. data) are evil. Their intentions are great. Except when the kid has to pass the test.

Part of why there is this disconnect with reality is that people, grassroots, are not part of the several official OLPC projects, despite proclamations in that sense. By design Dr. Negroponte wants to negotiate direct with governments. Later on, programs are set up that are quite top-down, with scant or no feedback expected, and certainly not encouraged, neither from teachers, nor parents.

Bottom line is that, the day the kid will have to take his test, he might, certainly have enjoyed more access to knowledge thanks to OLPC, but not the kind he will be tested on, and advice or opinion from those who really have a stake in the matter has not been sought.

No, we're not getting there. It will be an entertaining trip, but it will not help kids get where they will want to be.

what can we do

Listen. Answer. Discuss. In many countries administrators will assert truthfully that it is hard to get people to speak out, as an excuse for their own role in refusing them a voice. Alas, people who are uninformed think that computers by themselves are enough, or with the internet nothing can fail, or even ask for that proprietary operating system that almost sank OLPC.

Yet, if given the chance to know what is involved, the options, issues, and also a chance to say what they want, I dare believe that people would say they want their kids to have more curricular content, to have the machines help in certain areas of knowledge, to prepare them for what they understand is a better future.

I am deeply curious if the young people in OLPCorps Africa or the interns in Latin America are asking questions before they try to meld people to the OLPC ideology.

You forgot to ask the fundamental question: is buying a laptop the best way to improve education for elementary school children anywhere?

Can we invest that money in more productive educational initiatives, like building more schools or hiring more teachers or buying more school supplies or providing more training to teachers?

When you approach the problem (the "problem" is how to improve education) from this angle, it is much easier to see that the first step is to determine - through well-conducted, serious, independent studies - the actual benefits of one-to-one computer programs.

Mr. Negroponte is, quite naturally, opposed to this idea.

A few "well-conducted, serious, independent studies" are available, as the report "Flor de Ceibo", co-authored by Alicia Kachinovsky (http://www.flordeceibo.edu.uy/files/Informe%20Flor%20de%20Ceibo%202008.pdf ), published in april 2009. It appears that some of the weak aspects of the "Plan Ceibal" mentioned in this study, that deserves a wider publicity, are - at least in part - to be resolved: for example the lack of connectivity in/around the schools or in the houses of the schoolkids (see the recent bids initiated by the uruguayan LATU in order to provide an wider internet access in those areas), the creation of local/national educative contents (by the teachers themselves), the training of the teachers (see the participation of the "centros de formación docentes"), the addressing of the maintenance/repair/hotline issue (as the initiative around the "RAP Ceibal", or the inclusion of the private/secundary schools).

Sorry, Samy. That's definitely NOT a study. And the author clearly states so on page 4:

"En síntesis, los enunciados que se brindan en las páginas siguientes –afirmaciones,

cuestionamientos, conjeturas- son sólo hipótesis de trabajo para el 2009. Pretenden ser una

contribución para las autoridades del Plan Ceibal en su denodada tarea de implementación. En

cuanto a Flor de Ceibo, habrán de colaborar en la reformulación de sus intervenciones futuras, en

el ajuste de los instrumentos de registro y en el diseño de una estrategia de investigación. Como

dijo el poeta..."

@Irvin:

"Can we invest that money in more productive educational initiatives, like building more schools or hiring more teachers or buying more school supplies or providing more training to teachers?"

Please, expand on your plan to employ more teachers. Everybody tried this for half a century with no noticeably success.

But I understand from your comments you know how to do it for even less money than they want to spend on the laptops.

(I will not hold my breath over your answer as you have been asked this dozens of times before and you never ever responded)

Winter

Winter wrote:

"Please, expand on your plan to employ more teachers. Everybody tried this for half a century with no noticeably success."

Patently false, as always, Winter.

Israel, USA, Sweden, Japan, France, Canada, Spain, Singapore, Switzerland, Holland, Germany, Russia, Denmark and every other nation in the world has done it with traditional teachers, traditional schools and traditional methods.

That's the example that poor nations should emulate. After all, there is a very good reason why no developed country in the world has implemented Negroponte's "brilliant" idea...they know it doesn't work.

@Irvin,

"Israel, USA, Sweden, Japan, France, Canada, Spain, Singapore, Switzerland, Holland, Germany, Russia, Denmark and every other nation in the world has done it with traditional teachers, traditional schools and traditional methods."

Ignoring the plights of poor people, as usual Irvin.

It took a century or so to get universal schooling of children in the developed countries (most of the 19th century). Most countries got all children out of the sweat-shops and into the classrooms somewhere in the early 20th century, AFTER they became fully industrialized.

Moreover, these developed countries have had decreasing numbers of children in the last half century. So they could move their teachers with the baby-boom children.

Compare to Peru or Nigeria, which have increasing numbers of children and an already acute shortage of everything in education.

The 900 Million of children in the world with inadequate teaching need some 3-10 million EXTRA teachers. And they need them next year, not in 25 years.

But you and I discussed this already before, and you didn't care about these children then.

http://www.olpcnews.com/use_cases/education/olpc_xo_improve_teachers.html

(see your comments under the signature "rocco")

Winter

"Can we invest that money in more productive educational initiatives, like building more schools or hiring more teachers or buying more school supplies or providing more training to teachers?"

That's not a workable solution. For many decades developing states have known that they needed to spend sufficiently on education, and most of them just haven't done it. There is no way to persuade them to suddenly improve on this, nor any reason to think that they will change on their own. Nor is there any prospect whatsoever that the funds will be provided by outside parties.

Here's follow up to my comment above.

Irv, you proposed a solution that I think is clearly unworkable. That makes me think that this problem, namely education in the developing world, is one that you don't have a serious interest in, and haven't spent much time thinking about or reading up on, not recently and not prior to the olpc project starting.

Have I got that right? And if I am, is it your view that someone can have a correct understanding of this problem and what should be done about it without serious thought and study?

Oops, I accidently put my reply as a new thread below.

Eduardo montez wrote:

"That's not a workable solution. For many decades developing states have known that they needed to spend sufficiently on education, and most of them just haven't done it. There is no way to persuade them to suddenly improve on this, nor any reason to think that they will change on their own. Nor is there any prospect whatsoever that the funds will be provided by outside parties. "

I know that some countries won't spend enough money on education. That's true, but it has nothing to do with my post, if you care to read again and use your brain for a second.

I said that IF a country decides to spend money on education, it should consider doing what developed nations do (spend on schools, teachers and school supplies) instead of spending on unproven, dubious enterprises like OLPC.

Get it now?

@Irvin:

"I said that IF a country decides to spend money on education, it should consider doing what developed nations do (spend on schools, teachers and school supplies) instead of spending on unproven, dubious enterprises like OLPC."

No malice like real malice.

Now Irvin, what makes you think that developing counties spending money on teachers had anything to do with proven quality?

Where is the proof that spending money on teachers actually did improve education more than building cathedrals and burning witches helped against floods and famines?

Where are the scientific studies that say that spending more time in the classroom in smaller groups improves education?

Actually, such studies have been done. And I know what came out of it. But do you?

The fact that the US spends a lot of money on teachers says something about the unions and electorates, but nothing about effectiveness or quality. The USA have spend a lot of money on a Star Wars ABM shield, and we know how well that works.

Winter

Winter desperately asks:

"Where is the proof that spending money on teachers actually did improve education more than building cathedrals and burning witches helped against floods and famines?"

The proof is in every developed nation that you can think of: France, Germany, USA, Japan, Switzerland, Israel, Singapore, Canada, Sweden, Spain, etc., etc.

They rely - to this day - on schools, teachers and school supplies to educate their citizens, instead of foolishly giving their money to flight-by-night operations like OLPC.

Next childish question, please?

@Irvin:

"Winter desperately asks:

.....

The proof is in every developed nation that you can think of: France, Germany, USA, Japan, Switzerland, Israel, Singapore, Canada, Sweden, Spain, etc., etc."

Sorry, wrong answer. These are "common practices", just like burning witches and building cathedrals. Everybody "knew" these were the only recourse against floods, plagues, and famines.

It is obvious you do not want to present any strategy how the developing world can recruit and train the millions of teachers they need to educate their children in your "my way or the high-way" scheme.

Nor do you want to tell us how you "know" all these investments in teachers and buildings in the rich countries actually pay off. I have seen US High-Schools been described as "day-care centers for adolescents" (I wouldn't know, I have never visited one). So, maybe there are USAians that do not share your feeling about the pay-off from these investments.

You simply are not interested in "details" like that.

If you compare, eg, the educational systems in Japan, Sweden, Spain, etc., you will see that horrible amounts of time and money are spend on root learning&private teachers with very bad results (Japanese children learning English), a lot of time and effort goes into teaching Math&Literature to children that leave school (semi-)illiterate in reading and math (USA).

But we also see that many school systems really DO use computer technology in education (North-Western Europe) effectively. Others show that you can indeed get top-quality education with good teachers and methods (Eastern European countries).

This is all to show that there is no single, golden road to a good education for children. And not everything the rich spend money on is actually effectively, let alone efficiently, spend.

Winter

@Irv:

"I said that IF a country decides to spend money on education, it should consider doing what developed nations do (spend on schools, teachers and school supplies) instead of spending on unproven, dubious enterprises like OLPC."

Ok, I see I misintepreted what you were trying to say.

I think things are going to really take off a few years from now when the X0-2, or educational computers like it, become so cheap that enormous numbers of developing world families buy them on their own.

I say this for two sorts of reasons. On the one hand, developing world countries lack the funds, and generally also the competence and honest governance, needed to seriously improve their education systems. On the other hand, developing world parents have a deep interest in education for their children, and cheap educational computers chock full of self-instructional software will be an effective way to meet this end in the face of dysfunctional government educational systems.

As evidence, in one scene in the movie Slum Dog Millionare the two brothers attend a private school that their mother is paying for. I have read such schools are common in Indian slums, and are evidence of how much developing world parents wish to help their children learn.

I think when cheap education computers finally become available, poor parents will grab them up by the tens if not hundreds of millions.

Does anyone have any arguments why I'm wrong?

Does anyone have any arguments why I'm wrong?

Before I can answer that, it depends back on the fundamental question "What is the goal?" Is it to help a very poor "Under/non-developed" country, or a "developing" country?

Because for some very poor countries, even $100 is very expensive. $50 is very expensive. Some places education is a luxury that must be paid for through tuition. In developed countries, (say the United States), if parents thought a $100 device would drastically improve their child's education, many would most certainly buy it. As it is now, a huge percentage of US children have access to an internet-connected computer at home. Heck parents spend hundreds of dollars on game consoles, cell phones, and music players for their children. But not everyone has that disposable income. And of course it's not being made available to countries with this disposable income, which could demand the volumes that would encourage the drop in per unit price.

As well there's factors beyond the capital purchase of the machine. The machine works ideally with an internet connection. Internet, especially broadband, isn't accessible everywhere. Who will shoulder the cost? Though low power, the computers are more usable where there is access to an electrical grid (even if unreliable). Again, this isn't universal. As well who's going to support the machines in these markets. If an area doesn't have direct internet access, and there's an arrangement for "sneakernet" access to an internet cafe in a nearby town, that still takes coordination.

Let alone the logistics of actual academic work.

Good questions, John. However, I think the distinction between under/non-developed versus developing countries, while important, is not the right place to start out.

The first point is that the people of the world are roughly divided into three groups. At the top is the middle and upper class, about 1 or 1 1/2 billion. At the bottem is about a billion or so who are absolutely destitue. And in the middle is several billion who are poor but have some discretionary income, and use it to buy things like bicycle, motorbikes, refrigerators, tv's, cell phones and school tuition. And of course these class divisions cut across countries, with for instance India having large numbers in each group.

With regard to buying educational computers, each group must be looked at separately. The people in the middle group can afford to do it, and have motivation. And note there are other ways besides outright purchase, such as renting by the month, or two or more families sharing, or the head of an extended family buying one or more.

As to the destitute, the computers would have to be bought for them by outside parties, such as the government, foundations, or through foreign aid. By my calculations the cash total would be reasonable. Assume $75 a machine, 200 million families, each machine lasts 5 years and the purchase program is over 5 years, then the total per year is 3 billion. That's chicken feed.

As to wireless, it is becoming a lot more available. But it doesn't really matter. A child can still learn a great deal using an education computer that isn't hooked up to the internet.

Regarding electricity, the plan is the X0-2 will be human-powerable.

Regarding support, X0's are mostly child repairable. For things like software support I imagine it will spring up among the poor residents themselves, just like they do nowadays for, for instance, motorbike repair.

Regarding the logistics of academic work, the idea is to make the educational software self-instructional. Yes, that is not ideal, but it would still be a vast improvement over what these children are getting now.

I think this is an idea whose time has come. It's like how open source textbooks are suddenly taking off, or how cell phones have been spreading like wildfire in the developing world. I think in the next two or three years this idea is just going to take off like wildfire.

Dr. Mitra's TED talk has info relevant to this debate. See:

http://www.ted.com/talk/lang/eng/sugata_mitra_shows_how_kids_teach_themselves.html

Basically, if good teachers are not available or affordable, one or more computers might be the next best alternative. Some children can learn by themselves, given appropriate toys or tools. Some learning is better than no learning.

oops... correction to the link:

http://www.ted.com/talks/lang/eng/sugata_mitra_shows_how_kids_teach_themselves.html

A couple of points:

1) I'm not sure about other jurisdictions,but where we were in Kenya, the government pays for the teachers, but the community/parents must pay for the school's resources and infrastructure. That often means seeking sponsorship or support from elsewhere. In that regard, the teachers vs computers argument isn't terribly relevant since the teachers have a distinct funding source.

2) A library or classroom building can cost $20K and, at the end of construction, is still in need of books. That money will buy an awful lot of solar power, OLPC laptops, and SD cards - a virtual library that provides thousands of e-books per laptop and internet access to boot.

3) Cell phones are ubiquitous, and should give encouragement that populations in developing nations are as eager as the rest of the world to participate fully in the technological advances of the 21st century (in fact, the Safaricom cellphones in Kenya can do lots of things my provider here at home can't match - banking services for one thing!) The same arguments against the implementation of ICTs are the same arguments that people used to make against rolling out cell phone networks in the same locales.

4) Delivery of Internet through cell networks (using Edge and 3G) is already in place in lots of jurisdictions, and is easy to connect to the XOs and relatively inexpensive. Funding needs to be found for this data usage, but so does funding for books, bricks, mortar and latrines.

As the principal of the school we were working at said recently, "We need for further support and encouragement, so that we can reach your levels."

I can only speak from my experience, but everywhere I've visited, I've found teachers and students eager to participate in the technological revolution at hand. This doesn't obviate the need for good teachers, and rigorous curriculum - but it does speak to a the need for technological equality and efforts to speed the closing of the digital divide.

I read your article and the comments. First I'd like to say that two of my three children have received an XO laptop this year. We live in Uruguay and are witnesses of the development of this program and live it daily.

Because my children where already exposed to computers and have it available at home we thought having one would actually not make a big difference for them specifically. To our surprise we've seen improvement on other skills like reading and math just from using the games. My son 9 years old has figured out how to play different melodies with the music software it has and even made music sheets so his friends can know where the different notes are and play real music. Yes he is being taught music at home but what about all those other children that don't have a musical instrument? The XO can become a mean for children to find out earlier what they want to become.

Yes the need to instruct teachers is important and needed but don't think that all Uruguayan children have parents that are not cybernetic or with out computer knowledge. We didn't need a computer for our kids but we have seen the great advantages, the freedom it gives children to find their own solutions and we have seen the have learned from the experience so far.

For that reason only I speak from a user point of view and thank all those that had made this possible. Not only for my children but I know many, many who really have benefited from it.

Your comment confirms something that is widely known already, which is that it is among the families that do work with their kids, where the above-average parents make an effort to give their children better chances to learn that these 1-to-1 projects are most successful. Thank you, Karla, it's always good to have outside confirmation, as we have not yet settled on what we are sure of.

We want these projects to work also with those who do not have those blessings and support. With the 'botijas' that don't know what is best for them. Yes, you are right, the XO 'can become a means for the children', but it can also be one more distraction with little benefit (famous Romania study), for they do not have the structure and educated parental support. It is those kids that benefit most from learning content,as a recently published Stanford study demonstrates.

I am very happy about the advances in Uruguay. I had the opportunity to be at a meeting this Tuesday in Washignton DC where Vásquez and Brechner presented, and it was quite amazing.

My point here, and I said so to Miguel also, is that we should not forget the needs of those who are, as you well point not "cibernéticos", somewhat left behind because of certain policies.